Accurately valuing a closely-held business is arguably the most challenging part of the planning process. However, as with most items in the planning process, a business valuation does not have to be an overwhelming or impossible task. Ultimately, valuing a business is an art, not a hard science, so it is common to see a range of values or to encounter some “it depends” answers from advisors. For the purposes of this installment and our series, we will explore business valuation from a high level.

As with many items on our roadmap, it is essential to assemble a team of trusted advisors to assist with the business succession planning process. For this particular item, that team would certainly include your CPA and business appraiser. You might also include your attorney, wealth management professional, business banker, and possibly an investment banker/business broker in the discussion to ensure coordination.

Why You Need To Know The Value Of Your Company

Before we even start to consider the technical aspects of business valuation, let’s take a look at why it is a worthwhile endeavor. Business owners need to know the value of their business for many reasons, but setting the objectives of business transition planning may be the most foundational one. A business valuation goes a long way towards arming the business owner and advisors with the information and tools they will need to navigate the transition-planning journey. The initial questions we need to answer are:

- How much does the owner need from the sale of the business?

- Is the business worth enough to support the owner’s financial needs post-transition?

The answers to each of those questions will likely set off a chain of events, since value impacts who may be a potential buyer/successor, the transition timeline, and the structure and financing of the transfer. These topics are combined in this installment because business valuation and the owner’s goals are interrelated. You truly cannot have one without the other, especially when a business owner is planning for retirement and the proceeds of the business make up a large portion of the owner’s net worth. We will revisit the owner’s goals and concerns in a bit, but first let us take a very high-level look at a few of the more common business valuation approaches.

Look To Industry Valuation Methods

As mentioned above, business valuation is a challenging task that is certainly more art than science. Some have referred to business valuation as a “subjective science.” Subjectivity comes into play because, using the same financials, every buyer may arrive at different valuations because of their personal differences. Science is represented by standard, accepted valuation methods. In this section, we provide a very general summary of four common valuation methods, which should be a good starting point for additional discussions with your trusted advisors.

1. Profit Multiplier Approach

The profit multiplier approach, in its simplest terms, is just taking one number (i.e. profit) times another number (i.e. the multiplier) to arrive at the value of the business. Of course, there is so much more to the method, so let us start from the end, naturally!

First, we have to determine the multiple. If we are using pre-tax profit, the commonly applied multiple for closely held businesses might be between three and four, with multiples as high as five or more in special cases. Knowing which multiple to apply is the expertise that experienced business appraisers bring to the table.

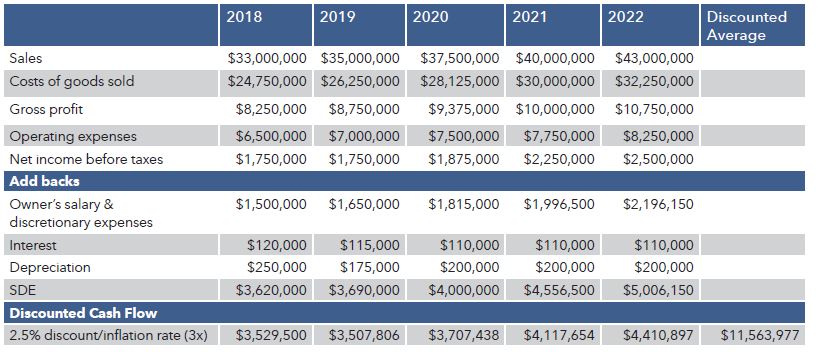

Second, we have to settle on a “profit” number. Generally, we see Seller’s Discretionary Earnings (SDE) used as the profit number in this valuation method. SDE starts with Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortization (EBITDA) and includes add backs for owner compensation, salary, profit-sharing, employer portion of payroll taxes based on owner’s salary, and discretionary expenses/perks for the owner. The discretionary expenses/perks category typically includes things like owner medical and life insurance, travel, meals, entertainment, vehicles, and club dues or memberships.

2. Discounted Cash Flow Method

The discounted cash flow method is somewhat similar to the profit multiplier approach. The main difference is the discounted cash flow method uses projected cash flow versus historic and, as a result, the method applies a discount rate (inflation) to calculate the present value of those future cash flows. As mentioned above, our intent is not to get lost in the minutiae of each method, so for our purposes let us focus on things that drive value up or down within the discounted cash flow method. First, since we are using projections, just how much profit is the business projected to make over the next given number of years? Second, how reliable are those projected profits?

3. Comparables Approach

This approach is similar to how residential realtors and appraisers value our houses. It uses transactional data to determine the value of a business. The sources of information/data include public company transactions, public company valuations, and private company transaction details that are publicly available. The goal is to emulate the arms-length transaction from actual, closed deals to prospect, real-world transition opportunities. As expected for anyone who has looked at residential comparables, the difficulty is finding actual comparable businesses.

4. Asset Valuation Approach

This approach adds up the equipment, real estate, buildings, cash, inventory, patents, goodwill, accounts receivable, etc. to calculate the overall asset value. It tends to serve as the baseline or starting point for valuation since a business that is a going-concern will be worth more than the sum of its tangible and intangible parts. However, for asset-heavy or struggling operations, it may be more appropriate.

Evaluate the Owner's Goals and Concerns

Each owner’s goals and concerns are 100% unique. Nothing can replicate or illustrate the owner’s introspection or provide the advisor with “special” insight other than his or her education, experience, and emotional intelligence. The ultimate pursuit in this endeavor is to help answer the question posed earlier, “How much does the owner need from the sale of the business?” In this section, we will first look at the comprehensive financial plan, as a whole, and then explore some of the pieces and nuances.

Owner’s Comprehensive Financial Plan

Using assumptions and projections for income, investment return, savings, lifestyle expenses, goals, needs, etc., a financial advisor builds a comprehensive financial plan. The objective is to forecast, with a reasonable degree of certainty, whether the owner will have enough money to live the kind of life desired. A financial plan “proves” the reasonable degree of certainty or confidence interval for success by running the client’s financial situation through a Monte Carlo simulation. As with any plan, the adage of “garbage in, garbage out” applies. Thus, no input is insignificant, especially when that input is likely the most valuable asset in a business owner’s portfolio – the business. However, the valuation of a business is anything but certain. Therefore, it is common practice to approach the planning process from the two perspectives discussed earlier:

- How much does the owner need from the sale of the business?

- Is the business worth enough to support the owner’s financial needs post-transition?

If you asked yourself those two questions and you answered with anything other than “I’m not sure,” then feel free to stop reading because you have already found a treasure chest. You may not be sure what, exactly, is in the treasure chest but it is a chest nonetheless. In the event you are skeptical, less than certain or just simply curious, please join us for the rest of our journey. We explored how much the business is worth above. However, the question of how much the business owner will need is, quite honestly, almost a complete guess. The reality is, for many business owners and for many people in general, the “how much do I need” question is impossible to answer. I would argue it is impossible because the question is neither fair nor complete. My initial response to the question is twofold: “it depends” and “when do I need it.” That sounds like a great place to start. Here are some general factors to consider in answering those questions:

- How much depends on what? (Family situation, health, age, mobility, independence, social circles, lifestyle)

- When do I need it? (All of the above and motivation, desire, aptitude, market conditions, economy, valuations, interest rates, outside savings, investments and assets)

The common theme throughout this series is that planning is an ongoing process. At any point, the delicate balance between proactive planning and reaction will swing seemingly without any outside influence. The pace of our society, market cycles, fads, etc. all highlight that change is constant. And today, change is really, really fast!

We tend to operate and plan with the mindset that we will get to “it” someday. What if we do not live to see “it”? What if we do, but we are not physically able to enjoy “it”? We have all put off something until tomorrow or next year. We have all heard loved ones, friends or colleagues say “someday.” A comprehensive financial plan need not be a deferral or a “someday” proclamation. Instead, the financial plan is the compass, the map, the North Star that charts the course, and it continues to guide us as we navigate (live) the obstacles (life) that pop up along the way.

Owner’s Challenges, Fears, And Issues Regarding The Transition

Just as business valuation is a subjective science, the entire business transition planning process demands a personal approach to properly address the various items of importance. For instance, a long-time business owner may be completely “set” financially, due to good planning and savvy investing outside of the business. However, he or she may struggle with the non-financial aspects of retirement and/or selling a business including:

- Identity issues (owner is the business/business is the owner)

- Giving up control

- Finding hobbies or other activities in retirement

- Pivoting from business owner to passive investor

The transition can be hard, if not impossible, for many business owners. Owners have spent their lives building that business. It is perfectly reasonable to struggle with the idea of what could possibly come next. However, an engaged and involved planning process should help ease that transition.

This installment is (hopefully) equal parts science and art. The moral of this and any other planning based story is this: you have to determine your desired destination before you efficiently plan to get there. Many aspects of business transition planning are moving at the same time. The goal for the business owner and the team of advisors should be to bring some synchronization and unity to all of those moving parts. At a minimum, those parts should all be moving towards the same desired destination.