Explore This Report With These Links

- Historic Government Shutdown Impacts Data Visibility

- Headline Strength, Underlying Strain: Inside Q3 GDP

- Fed Cuts Rates For A Third Time In 2025

- Signs Of Slack: The Labor Market Loses Momentum

- Key Inflation Rate Falls In November, But Data Collection Issues Raise Questions

- Consumer Confidence Ends The Year On A Sour Note

- Spending Resilience Amid Sentiment Slump

- Household Debt And Wealth Snapshot

- U.S. Tariff Revenue Surges To Record High

- $2.0 Trillion Projected Deficit For Fiscal 2026

- Key National Housing Data

- Eurozone Remains Resilient Despite Tariff Headwinds

- China Ends 2025 With Mixed Economic Signals

- Dollar’s Steepest Slide In Four Decades

- Market Commentary

- Selected Period Returns

- How Much Longer Can This Bull Market Run?

- Preparing For What Comes Next

Executive Summary

2025 was a year of contrasts with headline growth and tech-driven optimism coexisting with labor market cooling, geopolitical fragmentation, and structural imbalances. For investors, the key takeaway was resilience amid volatility, with opportunities concentrated in technology, energy transition, and selective global markets.

The third quarter gross domestic product (GDP) delivered a surprisingly strong 4.3% growth rate, at least based on the initial estimate, powered by consumer resilience and AI-driven investment. However, the delayed release and gaps in source data raise caution: revisions could be significant, and the apparent strength may mask underlying softness in labor markets and business investment. Policymakers and investors should treat this report as directionally positive but statistically fragile.

The Federal Reserve cut rates by 25 basis points in December, bringing the target range to 3.5%–3.75% to support a cooling labor market amid inflation and data gaps from the government shutdown. While markets rallied on the move, policymakers signaled a cautious path ahead with only two more cuts projected through 2027 and emphasized a data-dependent approach.

The 43-day government shutdown in Q4 was historically long and politically charged, with significant short-term economic disruption, furloughs, and service delays. While most spending will catch up, risks of permanent damage arose from threats of layoffs and delayed benefits.

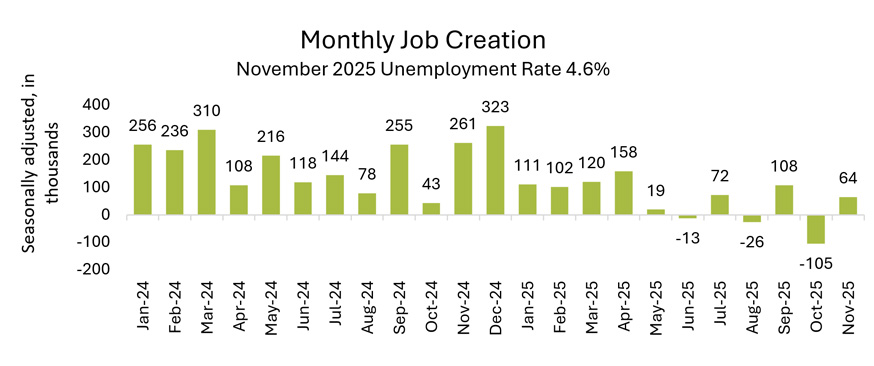

The November jobs report showed clear signs of cooling: the unemployment rate rose to 4.6%, its highest since 2021, while the broader U-6 measure climbed to 8.7% amid a surge in involuntary part-time work. Job gains have slowed dramatically—November added just 64,000 jobs after October’s net loss—and wage growth eased to 3.5%, the weakest since 2021, as quits and temporary-help employment fell to pre-pandemic lows. These trends point to a labor market shifting from tight to slack, increasing the likelihood of further Fed easing in 2026.

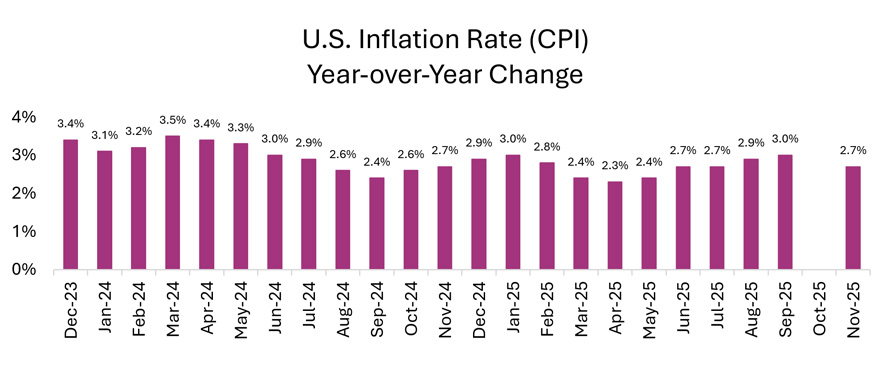

U.S. inflation eased to 2.7% in December, the lowest since July and below forecasts, but economists warn the decline stems largely from data gaps caused by a 43-day government shutdown rather than genuine disinflation. Missing October rent data and delayed November price checks, especially in housing, which drives a third of the Consumer Price Index (CPI), will distort readings for months, while holiday discounts may have exaggerated November’s softness.

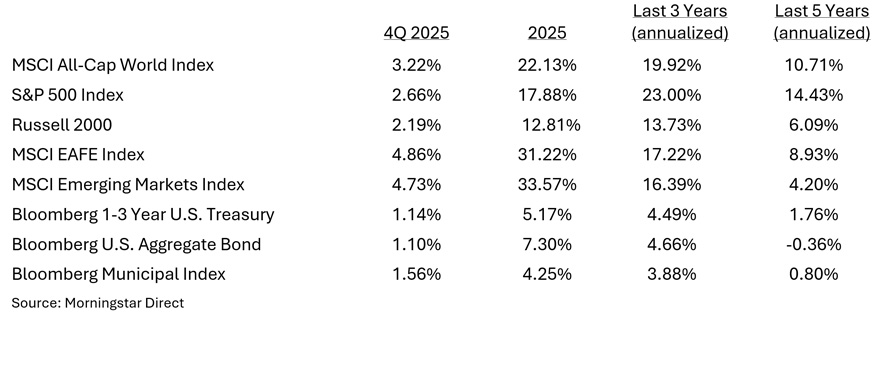

Markets proved remarkably resilient in 2025. After an early-year rally, a mid-year tariff shock rattled equities, but the Fed’s decisive pivot—three rate cuts in the second half—sparked a powerful rebound. The S&P 500 closed nearly 18% higher, small cap stocks nearly 13%, and developed and emerging international markets up over 31% and 33%, respectively. Fixed income markets staged a comeback in 2025 as falling inflation and three Federal Reserve rate cuts drove yields lower. The Bloomberg U.S. Aggregate Bond Index rose by 7.3%.

Historic Government Shutdown Impacts Data Visibility

The fourth quarter began, and was punctuated by, a government shutdown that lasted for 43 days, making it the longest in U.S. history. The shutdown was triggered by a failure to pass appropriations for fiscal year 2026 after the expiration of a continuing resolution. At the core of the dispute was a demand by Senate Democrats of an extension of Affordable Care Act premium tax credits. The eventual compromise extended funding for most agencies until January 30, 2026, and promised a December vote on health care subsidies. About 900,000 federal employees were furloughed, and two million worked without pay during the shutdown. Essential services including Social Security, Medicare, Transportation Security Administration, and military continued, but many agencies like National Institutes of Health and Centers for Disease Control faced partial or full suspension. Air travel disruptions and delays in economic data releases (e.g., jobs report, inflation, GDP) added operational strain. As a result, much of the economic data on which we rely is incomplete and will likely take many months to reconcile and validate before providing a clear picture of underlying economic trends.

Headline Strength, Underlying Strain: Inside Q3 GDP

Real GDP surged 4.3% annualized, the fastest pace in two years, driven by consumer spending (+3.5%), a rebound in exports (+8.8%), and increased government outlays (+2.2%). However, this strength masks underlying vulnerabilities: business investment slowed, residential investment fell for the fifth straight quarter, and labor market indicators weakened, signaling a disconnect between output and employment. The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) acknowledged delays in key source data (e.g., inventories, trade flows, corporate profits) and relied on imputed values and mixed methodologies to fill gaps.

Household spending remained resilient despite weakening confidence and rising unemployment. Consumer outlays increased across both services and goods. Within services, health care and other personal services were the primary drivers. On the goods side, recreational goods and vehicles, along with other nondurable items, led the gains. Overall, personal consumption contributed 2.39 percentage points to GDP. Capital expenditure growth moderated, yet AI-related investments in data centers, intellectual property, and equipment continued to provide meaningful support—reinforcing technology as a critical pillar of economic growth.

Government spending rose at both the state and local levels, as well as federally, with defense consumption expenditures leading the increase. Exports advanced across goods and services, while imports declined in goods—particularly nondurable consumer products—partially offset by higher service imports, led by business services. Net exports added 1.59 percentage points to GDP.

The Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Price Index, the Federal Reserve’s preferred gauge of inflation, rose 2.8%, with core PCE at 2.9%, both above the Fed’s 2% target. Price pressures in health care and services persisted, complicating the policy outlook despite easing from 2022 highs. The report was delayed nearly two months due to the government shutdown, replacing the usual advance and second estimates with a single initial release. BEA acknowledged reliance on imputed data and mixed methodologies, raising concerns about accuracy and potential downward revisions. Divergence between GDP (+4.3%) and GDI (+2.4%) further signals caution, as such gaps often precede revisions.

Services delivered a notable upside surprise in the latest GDP report, fueling the stronger-than-expected 4.3% growth in the third quarter. Earlier in the year, tariffs—and the rush by consumers and businesses to front-run them—blurred the picture of underlying momentum. But in Q3, services sent a clear signal of strength, expanding at a 3.7% seasonally adjusted annual rate, the fastest pace since Q3 2022 and a sharp rebound from the paltry 0.8% gain in Q1.

This performance carries extra weight because the U.S. is fundamentally a service-driven economy. Services account for nearly 47% of GDP and contributed 1.74 percentage points to the quarter’s growth.

The Institute for Supply Management’s Manufacturing Purchasing Managers Index (PMI) remained in contraction territory, coming in around 47.8 in December, up slightly from 47.4 in November. A reading below 50 indicates contraction. Sluggish global demand, inventory adjustments, and cautious capital spending have weighed on the sector, even as supply chains normalized and input costs eased. Overall, manufacturing remains under pressure, but the pace of contraction has slowed compared to earlier in the year.

Fed Cuts Rates For A Third Time In 2025

The Federal Reserve delivered its third consecutive 25-basis-point cut on December 10, lowering the federal funds target range to 3.50%–3.75%. The move, widely anticipated by markets, aimed to cushion a softening labor market amid still-elevated inflation and lingering uncertainty caused by missing economic data from the autumn government shutdown. Chair Powell likened policymaking to “driving in a fog,” underscoring the risks of aggressive action in an environment of incomplete information.

The decision was not unanimous: three FOMC members dissented—one favoring a larger 50-basis-point cut and two preferring no change—highlighting growing divisions within the committee. Alongside the rate cut, the Fed announced plans to resume Treasury bill purchases of roughly $40 billion per month to maintain liquidity and stabilize short-term funding markets.

Updated projections point to a cautious path ahead, with policymakers signaling only one additional cut in 2026 and another in 2027, suggesting a slower easing cycle. Markets expect the Fed to hold rates steady at the January 27–28 meeting following three consecutive cuts in late 2025. CME FedWatch assigns an ~80% probability of no change in January, with two quarter-point cuts anticipated by mid-2026.

Signs Of Slack: The Labor Market Loses Momentum

The U.S. unemployment rate increased to 4.6% in November 2025 from 4.4% in September, exceeding market expectations of 4.4% and marking the highest level since September 2021. The number of unemployed stood at 7.8 million, little changed from September, while employment levels were also broadly stable. The labor force participation rate was little changed at 62.5%, reflecting a largely steady labor force. The broader U-6 unemployment rate in the United States, which includes discouraged workers and those working part-time for economic reasons, rose to a seasonally adjusted 8.7% in November, reflecting a sharp increase in involuntary part-time employment.

The November jobs report reinforced the view that hiring demand is gradually cooling rather than rolling over. Job growth has moderated, wage pressures continue to ease, and there remains little evidence of broad-based layoffs across the economy. Monthly job gains have collapsed from an average of 139,000 earlier in 2025 to just 11,000 in recent months, with November adding only 64,000 jobs and October posting a net loss of 105,000. Manufacturing employment has dropped by 63,000 jobs year to date, with additional losses in transportation and leisure sectors, while health care remains the lone bright spot. Federal government employment fell by 271,000 jobs since January, amplifying private-sector weakness.

Quits rate—a measure of worker confidence—has fallen back to pre-pandemic lows, while temporary-help employment continues to decline, signaling employer caution. Wage growth slowed to 3.5% year over year, the weakest pace since 2021, even as inflation moderates.

The labor market is cooling across multiple dimensions: slower hiring, rising unemployment, weaker wage growth, and declining job quality. These trends, combined with large downward revisions and sectoral stress, suggest a transition from a tight labor market to one with growing slack, raising the likelihood of further Fed easing in 2026.

Key Inflation Rate Falls In November, But Data Collection Issues Raise Questions

The U.S. annual inflation rate eased to 2.7% in November 2025, its lowest level since July and below forecasts of 3.1%, as well as September’s 3% reading. However, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) did not collect data for October due to a 43-day government shutdown, leaving October figures permanently missing. Instead, the BLS reported that the CPI rose 0.2% over the two months from September to November, rather than providing the standard month-over-month changes.

Economists caution that November’s sharp drop likely reflects data disruptions rather than genuine economic shifts. These distortions complicate efforts by investors and policymakers to gauge inflation during a critical period, as major changes in trade, immigration, and fiscal policy ripple through the economy.

One of the biggest challenges lies in housing—a category that accounts for roughly one-third of the CPI basket. Because the BLS surveys rents on a six-month rotating basis, skipping October forced the BLS to carry forward September data, effectively assuming 0% inflation in October. Economists say this artificially depressed November reading will distort CPI until April 2026.

A BLS spokeswoman emphasized that the approach aligns with longstanding protocols and international standards for handling missing data. Still, additional distortions may persist. Price checks in November were delayed, meaning holiday discounts around Black Friday could have had an outsized impact on reported prices. These anomalies will carry forward, as November figures serve as a baseline for future calculations.

For investors, these anomalies complicate inflation tracking and could lead to mispriced expectations for Fed policy, increasing volatility in rates and equity markets until clearer data emerges.

Consumer Confidence Ends The Year On A Sour Note

December marked the fifth consecutive monthly decline in U.S. consumer confidence, with the Conference Board’s index slipping to 89.1 from November’s revised 92.9—well below expectations. Weakness was broad-based, as four of five components fell and net views on current business conditions turned negative for the first time since late 2024. Concerns about employment and household income weighed heavily on sentiment, echoing similar gloom in the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index. Both measures have trended lower throughout 2025, down 19% and 29% respectively over the past year, underscoring persistent anxiety about inflation, labor markets, and future economic conditions.

Spending Resilience Amid Sentiment Slump

Despite this pessimism, consumer spending, the backbone of U.S. economic activity, remained surprisingly robust in 2025. This “talk versus walk” paradox highlights a key disconnect: sentiment surveys reflect broad unease, but spending behavior tells a more resilient story. Households accelerated purchases of big-ticket items earlier in the year to front-run tariff hikes, and higher-income earners continued to drive outlays thanks to strong balance sheets and asset gains. Spending resilience masked widening inequality: high-income households drove outlays while lower-income cohorts cut back, reinforcing a “K-shaped” recovery pattern. Studies show that the top 10% of earners accounts for nearly half of all consumer spending, cushioning aggregate demand even as lower- and middle-income households report financial strain. Looking ahead, fiscal stimulus in early 2026 and solid equity fundamentals suggest that, historically, periods of weak sentiment have often preceded stronger market returns.

Household Debt And Wealth Snapshot

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s latest Household Debt and Credit Report shows that total household debt rose by $197 billion (1%) in Q3 2025, reaching $18.6 trillion. Delinquency rates remain elevated, with 4.5% of outstanding debt in some stages of delinquency. Early delinquency trends were mixed: credit card and student loan delinquencies increased, while most other categories declined.

A key source of stress continues to be federal student loans. Missed payments from the pandemic-era reporting pause (Q2 2020–Q4 2024) are now appearing on credit reports, keeping delinquency rates elevated after sharp increases earlier this year. In Q3, 9.4% of student debt was 90+ days delinquent or in default—up from 7.8% in Q1, though slightly below 10.2% in Q2.

To put this in perspective, U.S. households hold an estimated $197 trillion in total assets, including investment and retirement accounts as well as nonfinancial assets—primarily housing, which accounts for roughly one-third of household wealth. Against this backdrop, household net worth remains near record highs despite rising debt levels.

U.S. Tariff Revenue Surges To Record High

U.S. tariffs remain historically high, averaging an effective rate of about 17%, the steepest since the 1930s and up sharply from roughly 2% at the start of the year. Through November 2025, U.S. customs duties have soared to nearly $200 billion, more than double last year’s total and the highest on record. This surge reflects elevated tariff rates on steel, aluminum, autos, and broad-based imports under expanded trade measures. While tariffs have boosted government revenue, they have also added roughly 1.3% to consumer prices and increased costs for businesses, contributing to supply chain adjustments and reshoring trends. The sharp rise underscores tariffs’ dual role as both a fiscal tool and a source of economic friction heading into 2026.

Many countries now face baseline tariffs of 10–15%, with higher rates for nations targeted under “reciprocal” measures or national security claims. The 2025 tariffs fall most heavily on apparel, products with high metal content like electrical equipment and computers, and motor vehicles. Most tariffs were imposed under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) and Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, citing economic emergency and national security concerns. A major Supreme Court case on IEEPA tariffs is pending; if struck down, effective rates could fall by half.

$2.0 Trillion Projected Deficit For Fiscal 2026

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects the FY 2026 federal deficit to approach $2 trillion, or roughly 6% of GDP. A major contributor is the cost of servicing the national debt, which now totals nearly $1 trillion annually, making interest the third-largest federal expense after Social Security and Medicare.

Policy choices will shape the trajectory. For example, the extension of the 2017 tax cuts signed into law in July adds an estimated $4.6 trillion to deficits over the next decade, according to CBO. Advocates argue these extensions could deliver economic benefits: lower individual tax rates and expanded credits would boost household disposable income and support consumer spending—the largest driver of U.S. GDP. Business provisions, such as full expensing for equipment and the 20% pass-through deduction, may encourage investment, particularly among small firms and manufacturers. Dynamic scoring models suggest GDP could rise 0.5–0.7% in the near term, though the effect diminishes as debt pressures grow.

On the revenue side, elevated tariffs are generating record customs duties, but these collections offset only a fraction of the fiscal impact from tax and spending decisions. The challenge ahead lies in balancing growth-oriented policies with long-term fiscal sustainability—a debate that will remain central as lawmakers weigh priorities for 2026 and beyond.

Key National Housing Data

Home sales rose in November for the third consecutive month as easing mortgage rates injected fresh momentum into an otherwise stagnant housing market. Despite this recent uptick, activity remains subdued, with existing-home sales on track for a third straight year near three-decade lows. Lower mortgage rates, modest price declines, and a slight increase in supply have improved affordability for some buyers, but saving for a down payment remains the biggest hurdle for first-time purchasers.

Many prospective buyers are still frustrated by high home prices and uncertainty about job security, making them hesitant to commit to major purchases. Across the country, more home-purchase agreements are being canceled, reflecting an ongoing standoff between buyers and sellers. The average 30-year mortgage rate fell to about 6.15% in the fourth quarter, down from 7% earlier in the year. While this decline offers some relief, near-record home prices continue to keep affordability out of reach for many households.

Even so, falling mortgage rates have spurred more buying activity in recent months. Buyers are taking advantage of the modest improvement in affordability, and further rate declines could entice even more to enter the market—raising hopes that housing may finally show signs of life in 2026. On a year-over-year basis, however, November home sales were still down 1%.

Inventory trends remain mixed. The number of homes for sale fell 5.9% from October but rose 7.5% compared with November 2024. Increased supply has begun to push prices lower in parts of the South and West, yet overall inventory remains below pre-pandemic levels, keeping nationwide prices elevated. According to the National Association of Realtors, the national median existing home price in November was $409,200, up 1.2% from a year earlier but down from the $433,000 peak reached in June.

Eurozone Remains Resilient Despite Tariff Headwinds

The Eurozone continued to recover in the last half of 2025. Third quarter real GDP rose 0.3% for the quarter and 1.4% compared to a year ago, with fixed investment rebounding, government consumption firmer, and household consumption modest; net trade detracted as imports outpaced exports. Momentum into Q4 looks mildly positive based on surveys and sentiment indicators. Baseline projections see real GDP growth around 1.1–1.2% in 2026 with domestic demand as the primary driver while external demand gradually normalizes.

Domestic demand should remain the main driver of euro area growth, bolstered by rising real wages and record low unemployment. Additional government spending on infrastructure and defense, especially in Germany, alongside improved financing conditions stemming from monetary policy rate cuts since June 2024, is also expected to support the domestic economy. Inflation is projected to decrease from 2.1% in 2025 to 1.9% in 2026 and then to 1.8% in 2027, before rising to the European Central Bank’s medium-term target of 2% in 2028.

Germany, the largest economy, remains a swing factor. Germany’s central bank forecast that the economy, the largest in the Eurozone, would gradually recover in 2026 after three years of recession. The Bundesbank sees GDP growth accelerating to 0.6% in 2026 and 1.3% in 2027, driven by government spending and a resurgence of exports.

China Ends 2025 With Mixed Economic Signals

China’s economy closed the year on a cautious note. GDP growth is tracking near 5%, supported by exports and earlier stimulus measures, but domestic demand remains subdued. Industrial output rose 4.8% year over year in November, while retail sales grew just 1.3%, highlighting fragile consumption. Inflation pressures are minimal: December CPI edged up 0.1%, and PPI fell 2.3%, marking the 27th consecutive month of factory-gate price declines.

Policy remains accommodative, with Beijing maintaining proactive fiscal measures and targeted monetary easing to counter property-sector stress and deflation risks. Looking ahead, structural challenges—weak housing, soft consumer sentiment, and heavy reliance on external demand—pose headwinds, even as the newly approved Five-Year Plan emphasizes a shift toward consumption and innovation-driven growth.

China’s exports in 2025 showed surprising resilience, despite U.S. tariff actions. Shipments to the U.S. dropped nearly 20%, but exports to other markets more than offset this decline, pushing China’s trade surplus above $1 trillion. Despite official rhetoric on boosting domestic demand, China remains deeply tied to an export-led growth model, aided by supply-chain adjustments and market diversification.

In late December, China launched “Justice Mission 2025,” its largest military exercise around Taiwan since 2022. Chinese authorities described the drills as “stern warnings” to Taiwan’s independence advocates and nations offering external support, underscoring persistent geopolitical risks in the region.

Dollar’s Steepest Slide In Four Decades

The U.S. dollar index (DXY) surged to a three-year peak of 110 in January 2025, but by mid-September it had fallen to 96.6, a 12% drop—its sharpest annual decline since the Plaza Accord era of 1985. The reversal ended a structural bull run that spanned 2010–2024, with the first half of 2025 marking the worst six-month performance since 1973.

Key drivers included large fiscal deficits, unpredictable trade and tariff policies, and concerns over Federal Reserve independence, which eroded the dollar’s safe-haven appeal. Global investors rotated into Eurozone and Japanese assets amid dovish U.S. signals and stronger fiscal outlooks abroad. DXY closed out the year at 98.3, modestly above the year’s low. A weaker dollar brings mixed trade effects: U.S. exports become more competitive, while imports and foreign travel grow costlier for Americans.

Market Commentary

2025 was a year of extremes. The S&P 500 plunged more than 20% from its February highs following the announcement of sweeping tariffs in April. Shortly thereafter, a 90-day tariff pause was unveiled, triggering a stunning 9.5% single-day gain, the third-best day in the last 50 years. By late June, the index had fully recovered and went on to close up 17.9% for the year and 2.7% for the final quarter.

Large-cap stocks benefited from a powerful combination of AI enthusiasm, resilient corporate earnings, and solid economic growth. As in recent years, a significant share of returns came from outsized performance by a handful of mega-cap names. The so-called “Magnificent 7”—NVIDIA, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, Tesla, and Meta—generated a return of 23% as compared to the remaining 493 stocks which rose by 13%. The Seven account for 35% of the index, thus accounting for almost half of the S&P 500 price gain. Interestingly, only three of the seven outperformed the index. The biggest contributor was Alphabet, whose roughly 69% return added 2.72% to the index return, narrowly edging out NVIDIA’s 2.57% contribution.

Large-cap growth continued to dominate value in 2025, outperforming 22.2% versus 13.2% in 2025 and posting a cumulative gain of 133% versus 65% since the market low in October 2022. Mid-cap and small-cap results were more balanced between growth and value. From a sector perspective, communication services (+33.6%), technology (+24%), and industrials (+19.4%) all outperformed the S&P 500. Every sector finished in the black, with real estate (+2.7%) and consumer staples (+3.9%) bringing up the rear.

Small-cap stocks, typically more sensitive to interest rate movements, struggled early in the year but rebounded as expectations for rate cuts revived investor interest. By year-end, small caps were up 12.8%.

International markets significantly outperformed in 2025. The MSCI EAFE Index returned 31.2% in U.S. dollar terms, aided by a weaker dollar; in local currency, the return was 21.2%. Emerging markets led globally, surging 33.6% for the year.

Commodities delivered a standout performance in 2025, driven by inflation hedging and supply-demand imbalances. Precious metals led the charge as silver and platinum posted triple-digit gains and gold surged more than 60%, reflecting investor appetite for safe havens amid policy uncertainty and geopolitical tensions. Energy markets told a different story—oil prices softened in the second half as global growth concerns and easing supply constraints weighed on demand. Agricultural commodities saw mixed results, with weather volatility and trade disruptions shaping price action. The diversified Bloomberg Commodity Index returned 15.8% in 2025. Overall, 2025 reinforced commodities’ role as both a hedge and a source of tactical opportunity in diversified portfolios.

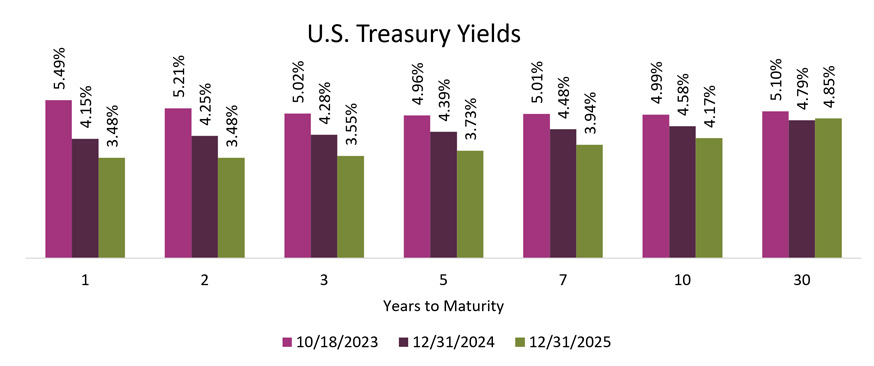

Fixed income markets rebounded in 2025 as cooling inflation and a decisive Federal Reserve pivot reshaped the rate landscape. Treasury yields declined across most of the curve following three rate cuts in the second half, driving strong gains across government and investment-grade bonds. Credit spreads tightened as recession fears eased, while demand for duration surged amid expectations of a prolonged easing cycle. By year-end, fixed income had reclaimed its role as a portfolio stabilizer, rewarding investors who stayed patient through volatility.

2025 saw a significant shift lower on the short end of the yield curve as the Fed initiated the rate-cutting cycle with three 25-basis point cuts. Short-dated bonds reflected these cuts with a decline in yield of 67 basis points this year. In contrast, the 10-year Treasury yield experienced a more modest decrease of 41 basis points, ending the year at 4.17%, indicating a mixed sentiment on long-term economic prospects. At the very long end of the curve, the 30-year Treasury yield rose by 6 basis points, pricing in potential higher inflation and increased fiscal deficits, signaling market concerns over long-term fiscal sustainability.

Selected Period Returns

How Much Longer Can This Bull Market Run?

The current bull market began on October 12, 2022, and is now more than three years old. It has navigated multiple challenges, supported by an economy that continues to grow, inflation and interest rates that have been trending lower, and strong corporate profitability. Over this period, the S&P 500 has delivered exceptional returns, rising 26.3% in 2023, 25% in 2024, and closing 2025 up 17.9%. That represents a cumulative gain of 86% or an average annual return of 23%. Along the way, the index set 57 all-time highs in 2024 and added more than 44 in 2025. The S&P 500 is trading at a strong earnings multiple of 22 times forward earnings. This is driven by a multiple of 29 times earnings for the 10 largest stocks in the S&P. Earnings growth for these large companies was strong in 2025 and expected to continue to increase. Pushing back against fears that AI was in a bubble phase, Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang recently reiterated his claim that the global annual spend on AI infrastructure can soar to $3-$4 trillion by 2030. He can make such a claim because the market for AI technology is changing and broadening dramatically.

History also provides useful context. Since World War II, there have been 13 bull markets, with an average gain of 164% and an average duration of 57 months, just under five years. More recent cycles have been even stronger. The five bull markets since 1980 averaged gains of about 240% over nearly six years. The longest bull market on record ran from 2009 to 2020, lasting 11 years and lifting stocks by 500%. It is worth noting, however, that the 2009 bull market began from deeply depressed valuations, whereas today’s market started from much higher levels.

Looking ahead, if interest rates continue to decline on mild inflation news, if earnings growth accelerates, and if the economy avoids recession, this bull market—driven by the performance of disruptive technology companies—may still have room to run.

Recent economic data suggests a gradual cooling in growth rather than an abrupt downturn. Regional manufacturing surveys and business activity softened, retail sales were flat, and housing sentiment remained subdued. Meanwhile, business inventories rose, and core consumer spending outside autos and gasoline held up better than expected—signaling demand is easing but not collapsing. The picture that emerges is one of deceleration, not contraction. The implication: while the economy is no longer running as hot as earlier in the cycle, current conditions remain consistent with a soft-landing path rather than an imminent recession.

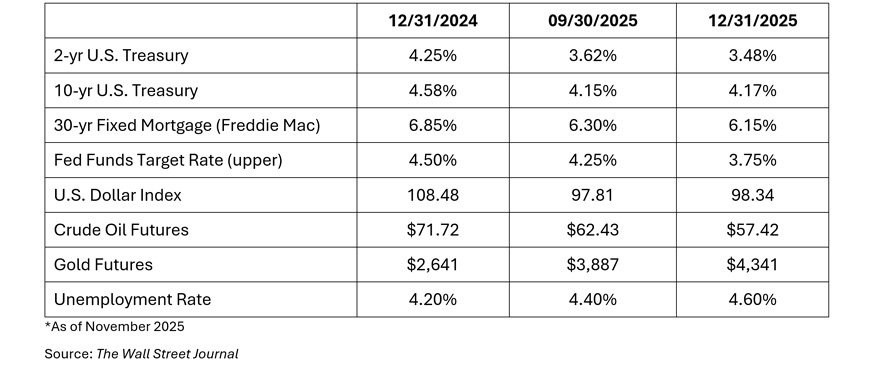

Key Rates

Preparing For What Comes Next

As we close the chapter on 2025, we want to express our deepest gratitude for your trust and partnership. This year reminded us that resilience and adaptability are the cornerstones of success—whether in markets or in life. Together, we navigated uncertainty, embraced innovation, and turned challenges into opportunities.

As we look ahead to 2026, we anticipate a year that will bring both opportunities and challenges. Innovation, particularly in artificial intelligence and clean energy, continues to open new paths for growth. At the same time, shifting interest rate policies, global trade dynamics, and geopolitical uncertainties underscore the importance of staying adaptable. Our commitment remains clear: to help you navigate this evolving landscape with confidence, turning challenges into catalysts for progress and positioning you to capture the opportunities ahead.

Looking forward, we remain committed to guiding you with clarity, confidence, and care. May the coming year bring you prosperity, peace, and moments of joy that matter most. Thank you for allowing us to be part of your journey—we are excited to continue building a brighter future with you in 2026 and beyond.

Wishing you and your loved ones a happy, healthy, and inspiring New Year!

First Business Bank – Ready When You Are.

Updated: 1/5/2026