The job market is waning, mostly due to a lack of workers, not demand for jobs. The U.S. economy added only 194,000 jobs in September, far below the consensus estimate of 500,000. The report is another sign that the spread of the Delta variant over the summer continues to have a negative impact on the economic recovery.

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, the shortages were very obvious to us with empty store shelves where toilet paper, flour, and beans should have been. Today’s worker shortages are obvious, too, if you have eaten at a restaurant, shopped for clothes, looked for daycare, or taken a flight.

Current Job Market Data

The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ monthly employment situation release presents statistics from two monthly surveys. The household survey measures labor force status, including unemployment, by demographic characteristics. The establishment survey measures nonfarm employment, hours, and earnings by industry.

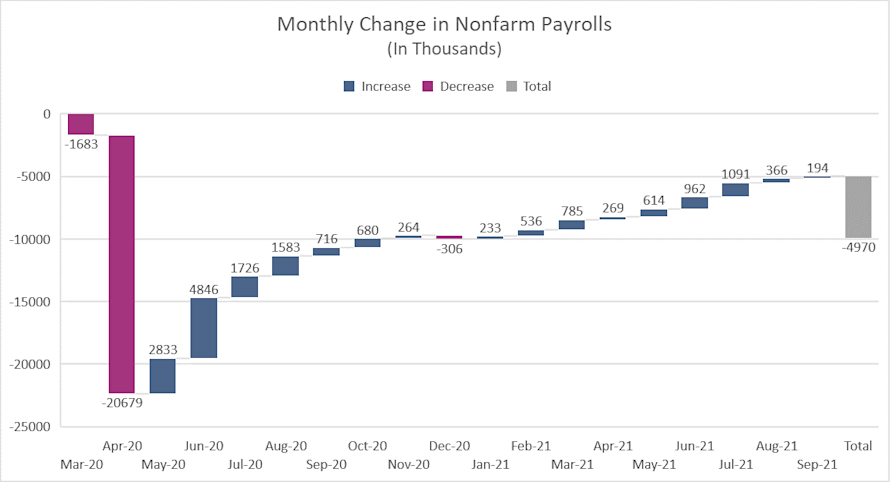

According to the establishment survey data, total nonfarm payroll employment increased by 194,000 in September. The July and August employment numbers were revised higher by a total of 169,000 jobs. Monthly job growth has averaged 561,000 in 2021 but has been uneven, as illustrated by the chart. Nonfarm employment has increased by 17.4 million since the trough in April 2020, but is down by almost 5 million from its pre-pandemic level.

Notable job gains in September occurred in leisure and hospitality, professional and business services, retail trade, and in transportation and warehousing.

Worker Shortages

September is typically a strong hiring month for public education, but in September of 2021 we saw a net loss of 166,000 state and local government education jobs. This is not due to a lower demand for teachers. In fact, July data shows 460,000 state and local education job openings — about twice as many as at any time before the pandemic. Versions of this theme are playing out in many industries. Several factors appear to be dampening hiring in some industries. Education, specifically, is a high-contact setting, so some concerned about COVID-19 have not returned to work and some eligible teachers have chosen to retire. Difficulties arranging childcare disproportionately affects women, and about three-quarters of schoolteachers are women. Worker shortages are disrupting many businesses, like restaurants, where the majority say they do not have sufficient staff to meet demand. Staffing shortages in the transportation industry are a major contributor to the supply chain difficulties plaguing the manufacturing and retail sectors.

The September household survey reflected a significant improvement in the unemployment rate, which fell by 0.4% to 4.8% in September. The number of unemployed persons, those actively seeking work, fell by 710,000 to 7.7 million. Both measures are down considerably from their early-pandemic highs at the end of the April 2020 recession, but are well above pre-pandemic levels.

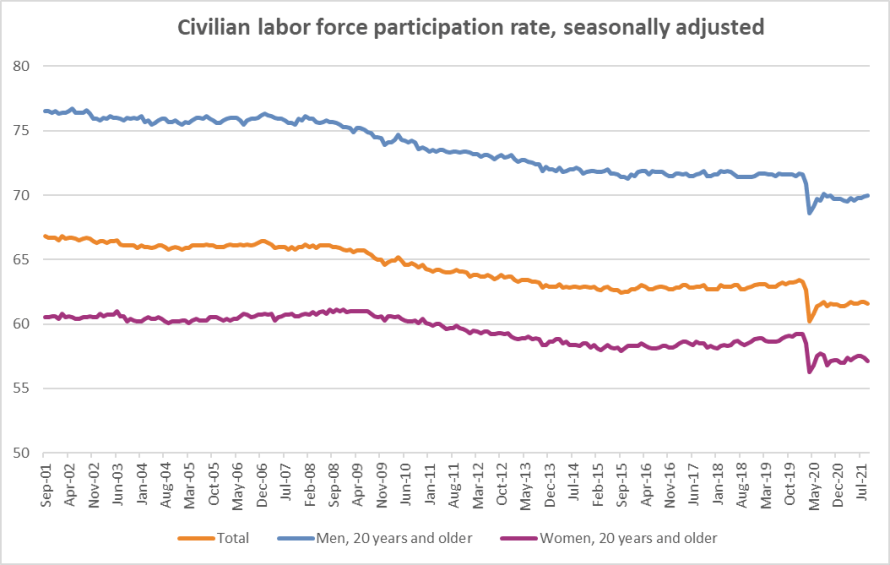

You may notice the disconnect between the decline in those actively seeking work (-710,000) and those who were hired (+194,000). The “labor force” consists of all employed and unemployed persons. Only those individuals who were actively seeking work during the last four weeks are counted among the unemployed. A declining unemployment rate is a good thing when it results from workers being hired. It is not positive when workers are leaving the labor force, even temporarily. As a percent of the total eligible population, the labor force participation rate is at 61.6% as of September. Labor force participation rose in the decades from the 1970s to 2000s. During this time, the biggest change was women’s participation rates, rising from 43.3% in 1970 to 62.2% in 2000. The overall rate has been declining since 2000 when it peaked at 66.8%. Pre-pandemic, the rate was 63.3%. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of persons not in the labor force who currently want a job was 6.0 million in September, little changed over the month, but up by 959,000 since February 2020. Among those not in the labor force in September, 1.6 million were prevented from looking for work due to the pandemic, little changed from August.

The Great Resignation

Recent data suggests that workers left their jobs at a record pace in August. “Quits” hit a new series high in data going back to December 2000, as 4.3 million workers left jobs. This is sometimes a sign of confidence in the availability of employment elsewhere, but many are evidently leaving jobs due to health concerns and other pandemic-related issues. In August, 1.3 million were discharged from jobs. This high number of employment separations, both voluntary and otherwise, minimizes the net new jobs numbers. Over the 12 months ending in August 2021, hires totaled 72.6 million and separations totaled 66.7 million, yielding a net employment gain of 5.9 million. These totals include workers who may have been hired and separated more than once during the year. It appears that the desire for flexibility and the ability to work remotely is the driving force behind some of the separations.

Ongoing Pandemic Problems

In May of 2020, the Bureau of Labor Statistics added questions to the Current Population Survey (CPS) to help gauge the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the labor market. These questions ask whether people teleworked or worked from home because of the pandemic; whether people were unable to work because their employers closed or lost business due to the pandemic; whether they were paid for that missed work; and whether the pandemic prevented job-seeking activities. Here are some highlights from the July 2021 report:

- 1 in 4 employed people teleworked or worked from home for pay because of the coronavirus pandemic. The share of the employed who teleworked has declined over the last three months. Full-time workers were almost twice as likely to telework as compared to part-time employees.

- 31.3 million people reported that they had been unable to work at some point in the last four weeks because their employer closed or lost business due to the coronavirus pandemic — that is, they did not work at all or worked fewer hours. This figure was down from 40.4 million in June and 49.8 million in May.

- Among people who reported that they were unable to work at some point in the last four weeks because of pandemic-related closures or lost business, 13% received at least some pay from their employer for the hours not worked.

- About 6.5 million people not in the labor force in July reported the pandemic prevented them from looking for work. This represents 7% of those not in the labor force. (To be counted as unemployed, by definition, people must either be actively looking for work or on temporary layoff.)

Based on this data, and on the results of the household survey, COVID-19 continues to play a role in weak employment gains as potential workers either lack the comfort level or the flexibility to seek work.

Earnings Increases

The number of new COVID-19 cases has fallen sharply in the last few weeks so we should see some positive movement in jobs data in the coming months. Average hourly earnings are trending higher — significantly in some areas plagued by worker shortages. Median hourly earnings increased 0.6% in September, causing the year-over-year increase to rise 4.6%. During the last six months, wages have averaged 6% annual gain — the fastest annual rate since the Bureau of Labor Statistics began tracking the measure in March 2007.

The labor shortage is just one headwind we face as we move into the latter part of 2021. A few solid months of stronger employment gains would be a welcome sign that the grip of COVID-19 is loosening.

We are pleased to bring our clients timely, relevant information that affects our everyday lives. Our doors are open and our phones are ready to visit about this or any other topic — give us a call or send us a message.